Ayelet Zohar and Ibrahim Nubani: Interview and Images

Simon Dawes interviews Ayelet Zohar on her article in the current issue of TCS (28.1, Jan 2011): ‘The Paintings of Ibrahim Nubani: Camouflage, Schizophrenia and Ambivalence - Eight Fragments’.

In discussing the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, schizophrenia and assimilation in the life and works of Ibrahim Nubani, Zohar includes Nubani’s own responses, taken from a recent conversation. This interview within an interview also features images of artworks by both Nubani and Zohar.

Image: Ibrahim Nubani, Untitled (2009), Pastel on Paper, 100X140 cm.

Simon Dawes: You make the link between Nubani’s status as a Palestinian-Israeli and his schizophrenic condition. Could you begin by explaining the difference between the term ‘Palestinian-Israeli’ and the more familiar ‘Arab-Israeli’, and then explain the link to schizophrenia, and how Fanon and Deleuze & Guattari help us understand it?

Ayelet Zohar: Arab-Israeli is the official term in Israel describing the minority population that belongs to Arab culture. The minority consists of several sub-groups that include Christian-Arabs, Muslim-Arabs and arguably, the Druze. [Only yesterday, Israeli court decided to grant Dr. Yakoub Halabi of the Druze village of osafiya, the right to register himself as Arab under the Nationality rubric, versus the common practice of registering Druze as a separate nationality. See: http://www.haaretz.co.il/hasite/spages/1215271.html [last accessed, Feb. 15, 2011].]

The members of the Arab groups are simply Palestinians, who lived in the place and never left their homes in the past century, but were the victims of historical changes in the area – from Ottoman Empire, to British mandate, and then the Zionist Jewish state. Palestine was never before an independent state, and it is still waiting for its moment in history.

Since the term Palestine or Palestinian was absent from Israeli vocabulary for many decades, including an official denial of such entity (“there’s no such thing as Palestine” is a comment still being heard among right-wing politicians and their supporters in Israel), the term Arab-Israeli served as a cultural softener to the dilemma regarding the identity of Israel’s largest minority. In the past twenty-thirty years, after the Palestinian voice became present and heard more clearly, there came to be an apparent insistence on the identity of the Arabs living in Israel (currently over 20% of the total population) as Palestinians, not just Arabs, maintaining their national (not just cultural) identity. These Palestinian-Israelis are not the more familiar Palestinian refugees who live in exile in the West Bank and Gaza strip (aka Occupied Territories), the neighbouring or other countries; these are actually Israeli citizens who share all aspects of daily life with Jewish-Israelis, including the right to vote and be elected to parliament, although still a deprived minority in many other aspects of life. To summarise – Palestinian-Israeli is the national-specific term that identifies and recognises the national and cultural history of Israel’s citizens of Arab cultural background, and Palestinian historical-political heritage.

Image: Ibrahim Nubani

When conversing with Ibrahim Nubani, he clearly indicates the problematic, somewhat schizophrenic aspect of this constellation: “from childhood”, says Nubani, “I was brought up by the education and civil systems of Israel as a Zionist (Jew) in a manner that completely denied and suppressed difference: we studied the history of Zionism, Hebrew literature, we went to the Kupat Holim clinic, and drank Tnuva milk. The Zionist project was all over the place, with no traces or signifiers of Palestinian/ Arab identity. The expectation from us, children and adults alike, was to identify with the Zionist state, which actually was the direct cause of the eradication of our previous lives as Palestinians (prior to 1948 - AZ). This became an unbearable state of affairs, which I call ‘schizophrenic reality’. For me”, says Nubani, “this very reality is the materialisation of my own schizophrenic experience.”

Schizophrenia in this context is implied in the Deleuzian & Guattarian meaning, as reflected through their employment of the term schizoanalysis: a (national) identity which (does not) exist, under constant tension with the (dominant) identity discourse of the ruling forces. The state of Israel made a long term effort to convince its Palestinian citizens to do away with their (false) identity. It is an immense psychological struggle that each and every Palestinian went though in life: the socialising systems in Israel are targeted to explain, justify and re-enforce the place as a Jewish state, a state that was constituted with only half-a-million Jewish citizens, just three years after the end of WW2. In those days, acknowledging the Palestinian identity within felt like a huge threat to the up-and-coming Jewish state. This sort of fear, combined with a clear understanding and knowledge of the immense damage done to the Palestinian population fills the minutes of official meetings, the diaries and writings of Zionist leaders of the time. I think that for long decades it was also the general opinion in Europe and the US. It was only after 1967 that this view dramatically altered, when it became clearer that the Jewish state was not such a fragile being, and that the refugees who were deported or fled Palestine during the 1948 war were no less victims then those who settled in Palestine at the earlier part of the 20th C. or after WW2. Growing up as a member of a minority group in a society which is always under the need to justify and validate its independence and presence, while the minority you belong to is constantly identified with the enemy, or the threat of the state’s being, despite the personal experience of being in a very weakened position with limited civil rights, can be a maddening experience. You can either choose to adopt the discourse of Zionism, imagine to be part of the ruling system (which Nubani did for the nearly three early decades of his life), but this can only be done if you hide and deny your original identity -- because it is being rejected by the same system that pretends to accept you, if only you convert. When Fanon is talking about the Black man wanting to become White, he exactly means this -- you can only be accepted if you convert / change your “colour”: if a Palestinian became a Zionist he would, presumably, be welcomed by the system, but in the long run, cracks appear in this method to the point of its failure. Bhabha, on the hand, is well aware of the rejection projected towards the “mimic man” – he is forever denied as “almost the same, but not quite”, and Bhabha correctly identifies the gap in similarity as motivated by racism and separationist discourse – “not quite, not White”.

This is the meaning of ‘schizophrenia’ in the cultural sense: disguise, blend, camouflage and becoming the Other. This is not just an external or temporal act of passing: if one performs in this manner for extended periods of time, the result is most probably the loss of clarity of one’s definite identity or being affiliated with a specific group or cause.

SD: The article is very much your interpretation of Nubani’s work and life, but to what extent does he agree with you? Were there any other, more personal, reasons for his initial collapse and condition?

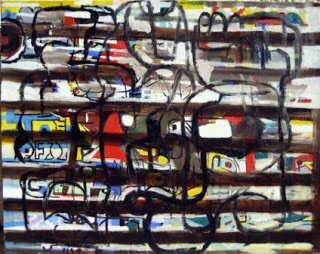

Image: Ibrahim Nubani, Untitled (2010), Oil on paper mounted on woodboard, 120X160 cm.

AZ: In the article, I counted the direct stages of Nubani’s life that led to his final collapse and schizophrenic fits: a rising career in Israel’s art world; a relationship with a Jewish woman; her refusal to get married with him, and his anger build up eventually leading towards the violent fits and aggression towards whoever he met.

In my recent conversation with Nubani, he states: “Being a Palestinian-Israeli is a socio-political problem. Socially, it indicates that the political regime in Israel refuses to understand the state of affairs of the Other, the human, the Palestinian. The political side indicates the power that denies the impossibility to exist as a Palestinian: the state structure of Israel is intended for Jews, not for Palestinians. As a child, I remember celebrating Independence Day [The Independence Day commemorates the declaration of the Jewish state, the day after British mandate in the region was stopped. In recent years, Palestinians in Israel commemorate the day as the day of Nakba – the Disaster of Palestine.], admiring Levi Eshkol [Israel’s Prime Minister between 1963-1969], or waving the blue-and-white David Star flag at the school yard on (Jewish) national holidays. The neighbourhood was filled with Zionist institutes like Bank Leumi (National Bank), Histadrut Zionit (Zionist unions) etc. From the day you are born you live through this kind of schizophrenic reality. The school educational programme was filled with subjects concerning Jewish History, Jewish literature, Jewish identity and nothing about our own dilemmas, history and suffering. I remember all through childhood wanting to become somebody else. This was always dictated by the daily reality around.”

“The difference between 1948 and 1967,” says Nubani, “is the type of occupation implied: the 1967 occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip maintained the military system and did not impose the state’s rules; the 1948 conquest was the occupation of our souls. Those living in the occupied territories, with all the pain involved, could uphold their Palestinian identity, while for us, the Palestinian-Israelis, the government, the system, always put much effort into converting us to pro-Israeli citizens. This realisation already grew in me when I was living in Tel Aviv (1980s –AZ). I remember talking about these difficulties with Yigal Tumarkin [A prominent Israeli Sculptor, Born in Germany 1933, immigrated to Israel in 1935, lives in Tel Aviv] who already recognised the absurdity of being Palestinian-Israeli early on”.

“Yasser Arafat said once: ‘You want me dead or alive, but I am a Shahid’ – I feel this is also the general attitude of the Jewish state towards us, Palestinian-Israelis: they do not want us dead nor alive, and simultaneously destroy our history and culture. The current ideas of the Zionist political parties sound to me like the lost paradigms of the 1950s of “pure” Zionism, with no minorities or presence of Others. They behave like whites against blacks, and using the system against us, our lives, our identity.

Image: Ibrahim Nubani, Untitled (2009-10), Oil on Canvas, 120X150cm.

Modern man is not a solid being – people move from one place to another, life becomes multilayered, with several identities, and one cannot erase the past. A man moves from one place to another, and becomes multifocal, or what I understand as schizophrenic”.

“And last, but not least, the occupation of Palestine first, and then the territories, is a colonial act that implies that power relations between (European) invaders and the local population that suffers under this colonial occupation. All these aspects are what make my identity schizophrenic, in direct relation to the power-imposing and self-denying reality I live through.”

SD: Your analyses of his paintings focus on his depiction of eyes and ocelli, and you draw on Lacan to interpret them as simultaneously a metaphor for castration and a metonym for the gaze (2011:19). Could you explain this double significance and the link to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict?

AZ: As seen from the previous reply, Nubani experiences his life as a process of denial, rejection and refutation. The psychoanalytical term for these feelings and experiences is castration, or an image that portrays the dismembering of the sexual (=life) drive, and the dignity of one’s own identity. Castration is a central figure in both Freud and Lacan’s discourses of denial and the violent experience of limitation and rejection one goes through in the process of growing up, denying one’s (original) desires, and the socialisation process that demands the displacement of one’s emotions and desires. Considering the state of mind of constant refusal and denial of one’s identity, castration seems to be the direct term relating to the psychological state of those relentlessly denied of their basic right for their cultural or political identity. The many eyes that occupy Nubani’s tableaux have become the image that symbolises this castration process, as was described by Freud in his text The Uncanny. Yet, as dissected eyes that stand alone and project a gaze, they also represent the detached gaze that travels away, to become an object that “looks back” at the viewer, hence, the eyes have a double – metaphoric (castration) and metonymic (gaze) role in these images.

SD: You cite UK research into the links between (increasing) schizophrenia among non-white ethnic minorities and the (decreasing) proportion of such minorities in the local population (2011:22-23), and refer to Fanon when you argue that ‘the more assimilated you are, the more vulnerable and exposed to rejection you become’ (2011:10). How do you interpret the consequences of this for political efforts to encourage assimilation and integration among minority groups in countries like the UK?

AZ: This is indeed, a major political and social issue, which I am not in a position to answer. All I can say here, is to quote Nubani, and refer to some knowledge collected through the Palestinian-Israeli experience. Circumstances of these specific relations, are very different to the conditions in the UK, however, one point, I think, can be drawn from this: it seems more and more relevant to understand mental conditions as derived from social and personal circumstances, and not just from one’s organic or medical history; therefore, the political and social climate is crucial for the well-being of one’s own life, making it a crucial, key endeavour to respect the personal history and social background of minority groups within the texture of the state’s majority. It seems that discourses of “Melting Pot”, “Social mosaic” and “Multiculturalism” still maintain a central, dominant discourse that represent the position of the social majority and the views of mainstream power that imposes an impossible reality and a demand to convert on those who either recently immigrated, or were forcefully joined into a society they did not choose to belong to. Transcultural discourses that externalise the gaps and differences, as well as conflict and disparity of aims, may well be needed in the process of multilayered, multifocal societies, with the obvious risk of disintegration of the nation-state into smaller entities built upon alternative ideals and discourses. With my humble view and experience I would say that it seems that establishing the large scale constitutional aims of democratic human rights as the common ground of society, while leaving specific cultural aims of minority groups to establish their own identity and values, may be the current possible path to follow.

Finally I would like to add the images of my own work of art as an extension to Nubani’s views.

Image: Ayelet Zohar, Lala Land (2010), ink and oil painting on plywood board, 122x244cm.

The first work, Lala Land (2010), is an image painted while living in residency in the Upper Galilee region of Israel, just below the Lebanese village of maroon al-Ras. In the image I portray the imposing presence of the mountain ridge with the village on top of it overlooking the grass lawn of my own yard, the mythological image of the Tel Hai stone lion, one of Zionism’s most famous symbols, adding a neon-light writing that reads Lala Land. This image is part of a series of five large scale paintings that depict the heavy tension and the consuming emotions involved in living under constant conflict.

Image: Ayelat Zohar’s Assimilation (2010)

Image: Ayelat Zohar’s Assimilation (2010)

The second work is an installation project entitled Assimilation (2010), which consists of a floating military, arctic camouflage net, floating over miniature ruins of stone houses scattered and dispersed into small heaps of separated stones. The inspiration for this project came from the village of Birim, a well known story of a village of Maronite Christians that were deported from their homes with a promise they could return in two weeks, a guarantee never fulfilled in the past 62 years. The village is now completely shattered and in wreckage, its citizens still hoping to come back someday and rebuild it from its ruins.

Read Ayelet Zohar's article ‘The Paintings of Ibrahim Nubani: Camouflage, Schizophrenia and Ambivalence - Eight Fragments' (TCS 28.1, Jan 2011)

Ayelet Zohar is an artist, curator and visual culture researcher based in the Galilee region of Israel. Zohar is a lecturer at the Art History Department of the University of Haifa (2011-) and is a fellow at the Van Leer Institute in Jerusalem (2010-). She was a post-doctoral fellow at StanfordUniversity (2007-9) and completed her PhD research titled ‘Strategies of Camouflage: Invisibility, Schizoanalysis and Multifocality in Contemporary Visual Art’ at the SladeSchool of Fine Art, UniversityCollege, London (2007).

Simon Dawes is the Editor of the TCS Website and Editorial Assistant of Theory, Culture & Society and Body & Society